Friday, March 24, 2006

a shining star for all to see...

tennessee supreme court justice adolpho birch, jr. announced his upcoming retirement from the court. justice birch has been the only judge on the court to honestly address and admit to the failures of the state's death penalty proportionality review and has consequently voted, usually as a lone dissenter, to overturn death sentences in this state. to be clear, he votes to uphold any conviction where constitutional or judicial error can not be found but votes to overturn death sentences because the state's proportionality review is an utter and abject failure.

tennessee supreme court justice adolpho birch, jr. announced his upcoming retirement from the court. justice birch has been the only judge on the court to honestly address and admit to the failures of the state's death penalty proportionality review and has consequently voted, usually as a lone dissenter, to overturn death sentences in this state. to be clear, he votes to uphold any conviction where constitutional or judicial error can not be found but votes to overturn death sentences because the state's proportionality review is an utter and abject failure.we will deeply miss the ethical standard justice birch has brought to the state's highest court...

Justice's law review

March 19, 2006

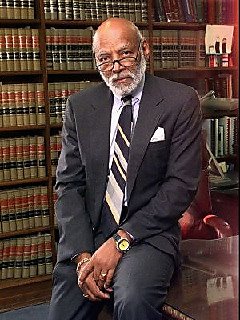

Tennessee Supreme Court Justice Adolpho A. Birch Jr., who became the state's first African-American chief justice in 1996, will end a 43-year judicial career when he retires at the end of August. Birch, 73, of Nashville, has spent 13 years as one of the five justices on the high court.

Birch, whom Gov. Phil Bredesen described as a "trailblazer," is the only Tennessee judge ever to have served at all levels of the court system -- General Sessions, Criminal Court, Court of Criminal Appeals and Supreme Court.

In a recent e-mail exchange with The Commercial Appeal, Birch recently responded to questions about his tenure on the Supreme Court and his earlier work as a civil rights-era lawyer. Here are excerpts from that conversation:

Q: Now that you are retiring from the Supreme Court, what is the one enduring memory you have of your service on the bench?

The one enduring memory I have is the collage of people who have helped and inspired me, and those whom I have, perhaps, inspired. I have had the enviable privilege of working with so many talented professionals. Along the way I have also met countless numbers of people with character and integrity. One regret is that I cannot thank each of them individually for the impact each has had on my career and my life.

Q: What do you consider the most significant case the court decided during your tenure?

Because I view all of the cases the Supreme Court decides as significant, I have made it a practice not to identify any one case as more significant than others. There is one, however, which had tremendous impact on education, and that case is Tennessee Small School Systems v. McWherter. That case held that the state had an obligation to maintain a public school system that afforded substantially equal educational opportunity to all students, regardless of their county of residence.

Q: What were your feelings about being the first African-American to serve as chief justice?

I always approach the "first black to do this or that" accolade with extreme caution. The reason is, for every "first one" there looms large in the past a host of others who tried but were rebuffed and rejected by unconstitutional laws and practice. I am ever mindful of the sacrifices those forebears made, and I fully realize I stand upon their broad shoulders. But for their sacrifices, none of this would have been possible.

Q: You've been criticized in the past as being against the death penalty and faced an organized effort several years ago to oust you from the bench primarily because of your death penalty rulings. What are your overall views about the death penalty?

My overall views of Tennessee's death penalty protocol are available for inspection in the Southwestern Reporter (encyclopedia of case law), beginning with the Second Series. Not to be curt, but I'm sure you understand that this is all I can say.

Q: As a lawyer in Nashville in the 1960s, you handled a lot of civil rights cases. What was it like as an African-American attorney in those days, representing lunch-counter protesters and citizens seeking basic civil rights?

It was indeed tough to represent lunch-counter protesters and others who sought to enforce their constitutional rights. Any black lawyer who practiced in the South in the '50s and '60s can attest to the discourteous, rude and insulting treatment accorded both client and lawyer. Indeed, if not insulted, we were ignored. This dismissive treatment intensified because of the frontal attack on unconstitutional practices.

Q: When most people think of the leaders of the civil rights movement, they naturally think of black preachers such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others who were at the forefront. Talk about the significant impact that black lawyers had on the movement as well.

Black lawyers were the architects of the civil rights movement -- Charles Houston, William Hastie, Thurgood Marshall, Constance Motley, James Nabrit. It was their blueprint, unerringly followed, that culminated in the monumental decision in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

Q: As someone who has been part of the judicial system for so long and has witnessed so much change for the better, why do you think so many African-Americans still believe the system remains unfair to them?

I think the perception of unfairness in the judicial system is more informed by "class" divisions and economic factors than "pure" racial discrimination. Admittedly, there is much overlap and blurring of lines, but if you can agree that "rich" and "poor" are values that have different meanings for different individuals, then "fair" and "unfair" must be subjected to the same analysis.

Q: What advice do you give young people who may be interested in a career in law?

Decide to invest every ounce of your being into its study and practice; 99 percent just won't do.

Q: What are your plans after retirement?

Nothing definite. I do have four grandchildren who are a source of great joy for me.